Caecilia Pieri, Bagdad. La construction d`une capitale moderne, 1914-1960 (Beyrouth : Presses de l’Ifpo, 2015).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this book?

Caecilia Pieri (CP): Having seized an opportunity to go to Baghdad in June 2003,[1] I unexpectedly discovered an interesting modern vernacular landscape, which remains important to this day—in terms of quality and, still today, in terms of quantity. Instead of the black hole of information and of desolation with which the city’s name was associated due to the war(s) and sanctions, I saw a modern city which possessed a human shape, whose brickwork and concrete architecture revealed a civilian life, a subtle, rich and sophisticated sociability, and a thriving creativity. It was the contrary of the distorted military imagery overshadowing them over the last decades.

[Top: Villa Chadirji, built 1935-1936 by Badri Qadah, a Syrian architect who got his diplomas from the Ecole de Génie Civil in 1928, then from the Institut d’urbanisme in 1930, both in Paris. Photo by Caecilia Pieri, 2012.

Bottom: Mmouniya School, Waziriya, Baghdad, built 1952. Architect: Hazim al-Tik (1927-2015). Photo from student file by Haidar Lutfi, Sara Salih, Marwa Falih, Shimiran Taidi, Baghdad College of Engineering. ]

Upon returning from my first trip in 2003, I started seeking to document my first photographs. I immediately was confronted with the following fact: contemporary Baghdad was, as Pierre-Jean Luizard had already written at the time of the embargo, “almost absent from the field of publishing.” Concerning the built work, critical literature is especially devolved to the archaeological periods, and Islamic eras and cultures (Abbassids, Persian) as well as, to a lesser extent, the Ottoman era. There are few studies on the contemporary era, as the term is understood by historians. This book is the fruit of an intellectual curiosity born from the shock of my senses. I decided to dig deeper into the question in order to help make understandable the urban form and city life of a city too often perceived through either un-informed or deforming lenses—that is to say, of a too-little-known city. It is also the starting point of a militant way to construct this built ensemble as a modern valuable heritage and to raise public awareness about it, in Iraq and outside Iraq. I have traveled nineteen times to Baghdad between 2003 and 2013, each stay being rather demanding in terms of organization: precautions, discretion, security, for me and for people hosting me. It did not make the task easy to realize surveys, interviews, and researches.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

CP: Baghdad’s evolution cannot be dissociated from Iraq’s specific political context. The capital’s evolution between 1914 and 1960, between urban development and national construction, echoes the dynamics of state-building and nation-building. The paradigms I studied are framed within the crossing of several perspectives. First, there is what belongs to the history of cities: morphological evolution, typology, topographical and functional singularity—among others, I have identified a paradigmatic Baghdadi “urban cottage” (in the Thirties) which is to Baghdad what the “three arches house” was to Beirut.

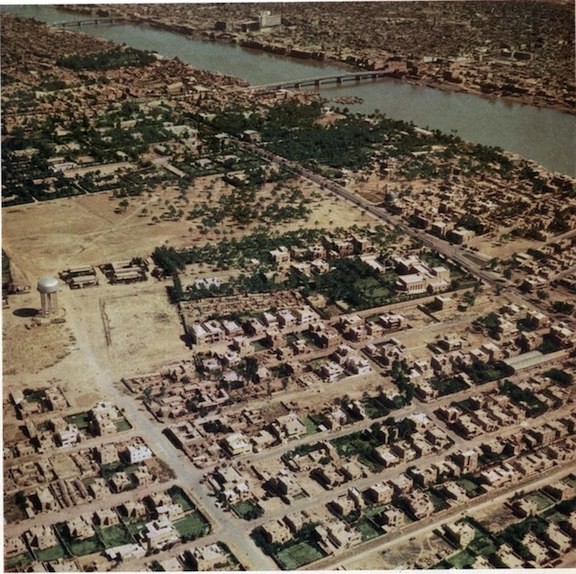

[Aerial view of Baghdad showing the regular “garden” city as planned after 1935, with detached or semi-detached “urban cottages.” Karradat Maryam neighborhood (today: the Green Zone) Source: Land of the Two Rivers, 1957.]

My approach also includes urban anthropology. It is a history of individual and collective practices at various scales: house, neighborhood, and city. The backdrop to my analysis is a third perspective: the history of policies regarding the physical organization of the city as well as how they were perceived. Finally, there is an overlaying approach which is sensitive to cultural and artistic history, through the attention given to styles and decors, and the aesthetic and technical processes.

This book also largely tries to decode Iraqi historiography; this work is essential given how few primary sources there are, and extremely delicate due to the ideology that has prevailed for several decades. I found very few sources, often unreliable ones, such as official and academic publications rigged by a national discourse and representations: this constituted both an exciting and a perilous interpretative obstacle course. This book also exhumes precious primary archives gathered in Iraq and in Europe that have never been published before.

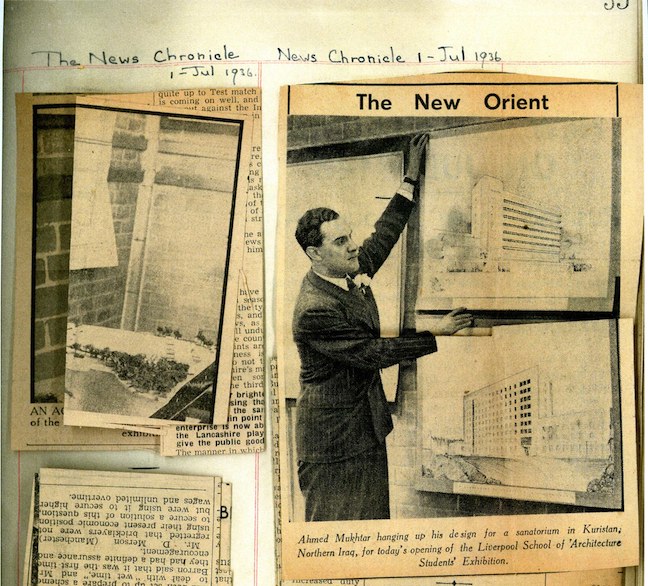

[Ahmad Mukhtar Ibrahim, the first Iraqi who graduated as an architect in Europe, showing his diploma, a sanatorium for the Kurdistan region, where he was born (detail). Source: The News Chronicle, 1 July 1936. Archives, Sydney Jones Library, Liverpool.]

Finally, I am trying to roughly identify the technical modernization processes at play in Baghdad, while trying to understand the extent to which a real modernity (as a cultural condition) was setting in or not. My understanding of “real modernity” is the ultra-relative and thereby universal definition given by Gwendolyn Wright: what is modernity, if not dealing with the Other’s difference?

J. How does this book connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

CP: Most of the book proceeds from a PhD defended in 2010 at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris; but I took the time to add historical documentation (most of it is unpublished or consists in reprints of old magazines, books, and maps) that was not in the dissertation. Previously, I had graduated long ago in History and Literature, and then I was a senior editor in the field of architecture and heritage for over twenty years. When I resumed my studies with my research on Baghdad, I put into practice the methodology and critical investigation I had been editing in the texts of my authors. But the book and the research are part of a wider scope. One of my main concerns is to be an activist in the field of urban heritage. Working on Baghdad gave me a solid knowledge, and added to my experience as an editor, then as the Head of the Urban Observatory (four years, French Institute of the Near-East, based in Beirut, dealing with Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, the Palestinian Territories, and Jordan). Finally, I am part of the steering committee of UNESCO-MUAMA-World Heritage group (for the safeguarding of modern urban and architectural Arab heritage).

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

CP: Iraqis, first, of course, as most of them are aware of general ideas or specific details. However, because of the political and security situation for decades, few of them were able to create a link between on-site work and archival research after the 1970s. Having had the privilege to be able to do both, I hope to give some coherence to what was the “missing link” between pieces of information dispersed between Arabic and European sources, because these sources are geographically disseminated.

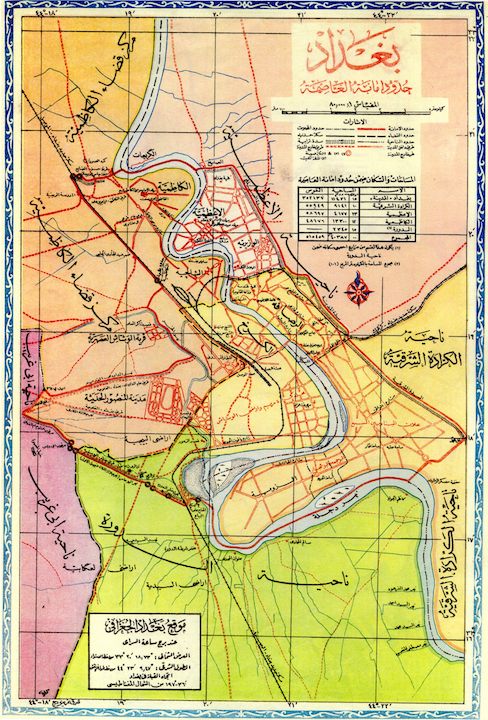

[Map of Baghdad in 1952, before any further masterplan. Source: Ahmad Susa, Atlas Baghdad, 1957.]

Far beyond the Iraqi audience, I think that this history of modern Baghdad can bring a useful complementary piece to the history of the modern Middle East in general, far away from the usual orientalist clichés of nostalgia and the loss of the 1001 Nights.

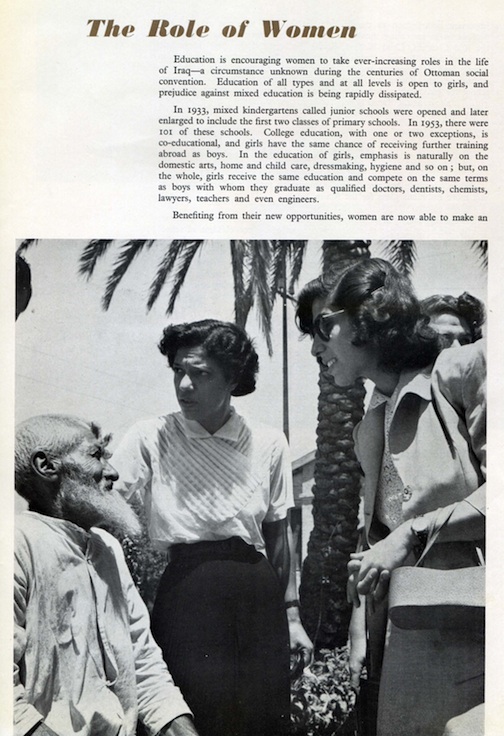

[“The role of women” in modern Baghdad under the Monarchy. Source: Land of the Two Rivers, 1957.]

J: What other projects are you working on now?

CP: At the crossing between political geography and urban anthropology, I would be interested in working on Baghdad in the framework of divided cities or post-conflict cities (Bollens). The post-2003 urban configuration bears witness to an unprecedented level of spatial segregation based on politicized religious identities. Mutatis mutandis, it recalls the tribal fragmentation of the pre-modern city by reactivating the ‘assabiyat (primary belongings) to compensate the failure of the central state. But this would require a collaboration with local correspondents and is currently complicated by security matters, and by the growing numbers of emigrants. I don’t know if I will be able to continue.

Also, I am part of two research programs: one as a member, in Beirut, dealing with the role of universities and the process of urban production (associating ALBA and Université Rennes II); and the second as the research coordinator, on “Heritage at War in the Mediterranean Region,” involving partners in Lebanon, Turkey, Italy, Bosnia, Algeria, and Egypt (AUF/ Ifpo, 2015-2017).

Excerpt from Bagdad. La construction d’une capitale moderne, 1914-1960

La révolution a ouvert une page radicalement nouvelle dans l’histoire des rapports entre l’artiste et le pouvoir en Irak. Peintre ou architecte, celui-ci y acquiert un nouveau statut, une stature officielle. Soutien, mais aussi devoir. […]. Dès la révolution, la politique se mêle étroitement d’image : Chadirji raconte dans ses mémoires comment, une fois obtenue la commande de ce monument qui devait célébrer la rupture avec les chaînes du passé, le groupe d’artistes a eu affaire à des pressions constantes et précises pour influer sur le détail. Le ministère de la Défense ainsi qu’un comité central pour la communication officielle essayèrent notamment de les convaincre de représenter Abdelkarim Kassem lui-même…Un compromis a été finalement trouvé en plaçant, au centre de la composition (dont la forme s’inspire des banderoles déployées par les manifestants en 1958),[2] un soldat symbolisant le rôle libérateur de l’armée (Chadirji 1991 : 106-108).

Vingt ans plus tard, Saddam Hussein convoquera sculpteurs et architectes pour refaçonner Bagdad, en grand maître d’une cérémonie urbaine dont lui-même aura fixé tous les rituels et tous les détails. L’ordre du pouvoir sera sans discussion et l’architecte ne servira plus directement la nation, n’ayant guère le choix qu’entre l’exil et le service d’un pouvoir absolu prétendant incarner, à lui seul, la nation.[3]

Par la révolution de juillet 1958 l’Irak avait pu « acter » son indépendance—en architecture comme en politique. Or, au plan des populations et des mentalités qui habitent et façonnent la ville au quotidien, la Bagdad qui émerge de cette révolution n’est déjà plus la « cité des pluralités » dont rêve encore Jabra Ibrahîm Jabra en 1988. Dans un article, au titre révélateur de « Baghdad in a perspective of time », Jabra exprime notamment, à travers l’évocation idéalisée de Babylone, sa nostalgie d’une ville de l’Orient arabe traditionnel. On comprend entre les lignes qu’il s’agit de Bagdad—et que cette Bagdad-là n’est plus:[4]

« Babylone, de fait, fut la première métropole de l’histoire ; la ville des pluralités, ouverte sur l’extérieur, capable de maintenir ensemble sous une forme dynamique et viable un grand nombre d’éléments disparates, tant culturels qu’humains—différentes races, religions, langages, vivant tous rassemblés sous la protection d’une organisation centrale et d’une culture dominante. »[5]

On peut réévaluer l’histoire, mais on ne peut pas la réécrire. La question que l’on peut dès lors poser pour l’Irak d’après 1958 est la suivante : peut-on bâtir, au sens propre comme au sens figuré, une nation moderne, et donc une capitale (ou une métropole) moderne, avec seulement des éléments homogènes ? Au lendemain de la révolution, cet équilibre instable a inspiré à un observateur cette réflexion lapidaire : « Mêlés, mais non amalgamés ; Hindous, Juifs, Kurdes, Turcomans, Arabes… Ceux qui divisent pour régner ont ici le travail facile. » (Loverdo 1961 : 136). Jusqu’alors, la diversité n’était pas problématique en soi dans la construction nationale irakienne. À partir de 1958, la question désormais sera celle de la gestion politique de l’hétérogénéité.

Mais on touche ici à la nature même du politique, et ceci est un autre débat.

English Translation (Translated by Esther Spitz)

The revolution opened a radical new era in the history of the relationship between artists and power in Iraq. Painters and architects acquired a new status, an official stature, implying support and duty. […] Politics were intricately laced with image ever since the revolution: Chadirji recounts in his memoires how the group of artists who was contracted to build the monument celebrating the severing of ties with the past (on Tahrir Square) immediately became the target of constant and precise pressures looking to influence the detail. The Ministry of Defense, as well as an official communication central committee tried, among other things, to convince them to depict Abdelkarim Kassem himself…A compromise was eventually found, by placing at the center of the composition (whose shape is inspired by the banners deployed by the 1958 demonstrators),[6] a soldier symbolizing the army’s freeing role (Chadirji, 1991: 106-108).

Twenty years later, Saddam Hussein called on sculptors and architects to remodel Baghdad, setting himself as the master of an urban ceremony where he set all the rituals and all the details. The power was not questioned and so, the architect did not serve directly the nation anymore: he only had a choice between exile and the service of an absolute power claiming to solely embody the nation.[7]

Through the July 1958 revolution, Iraq was able to realize its independence—in architecture and in politics alike. However, regarding the populations and the mentalities inhabiting and shaping the city on a daily basis, the Baghdad which emerges from that revolution is already far from the “city of pluralities” Jabra Ibrahîm Jabra still dreamed of in 1988. In an article with the very telling title of “Baghdad in a Perspective of Time,” Jabra expresses, through the idealized evocation of Babylon, his nostalgia for a traditional city from the Arab Orient. We understand between the lines that he is writing about Baghdad—and that this Baghdad does not exist anymore:

“Babylon, in fact, was the first metropolis in history: the outward-oriented city of pluralities, capable of holding together in a viable and dynamic form a vast number of disparate elements, both human and cultural. Different races, religions, languages, all living together under the protection of one central organization and one dominant culture.”[8]

We can reevaluate history, but we cannot rewrite it. When talking about post-1958 Iraq, the question is: can we build, literally as well as figuratively, a modern nation and therefore a modern capital (or a metropolis), only with homogenous elements? In the wake of the revolution, this unstable equilibrium inspired the following lapidary comment: “Mixed up, but not blended together; Hindus, Jews, Kurds, Turkmen, Arabs…Those who practice the ‘divide and rule’ principle have an easy job here” (Loverdo, 1961: 136).

Until then, diversity was not a problem in itself in the Iraqi construction. From 1958, the question will now be about the political management of heterogeneity.

But here we are touching on the very nature of politics, and that is another debate.

[Excerpted from Caecilia Pieri, Bagdad. La construction d’une capitale moderne, 1914-1960, by permission of the author. © 2015 Institut français du Proche-Orient. For more information, or to purchase this book, click here.]

NOTES

[1] In order to meet contemporary Iraqi painters. This trip was to lead, the following October in Paris (Galerie M), to an exhibition and the publication of a catalogue, Bagdad Renaissance, Art contemporain en Irak, Jean-Michel Place Publication, Paris, 2003, 96 p.

[2] Entretien avec R. Chadirji à Londres, 15 juillet 2009.

[3] Le détail de ces grands projets est publié dans Process Architecture 1985, cf. bibliographie Fethi 1985 ; une partie d’entre eux est commentée dans Luizard 1994, Makiya 2004 et Pieri 2008.

[4] Sur l’ambiguïté du rapport entre critique et pouvoir sous Saddam Hussein, lire Pieri 2015.

[5] “Babylon, in fact, was the first metropolis in history: the outward-oriented city of pluralities, capable of holding together in a viable and dynamic form a vast number of disparate elements, both human and cultural. Different races, religions, languages, all living together under the protection of one central organization and one dominant culture.”

[6] Interview with R. Chadirji in London, July 15th 2009.

[7] The detail of those projects is published in Process Architecture 1985, cf. bibliography in Fethi 1985 ; part of them is commented upon in Luizard 1994, Makiya 2004 et Pieri 2008.

[8] On the ambiguity of the relationship between critics and power under Saddam Hussein, see Pieri 2015.